If you were asked to pinpoint a scientist in a crowd, how would you recognize one? Or if you were asked to identify a scientific publication among other books, how would you be able to do so? And what would you do if you were asked to identify scientists, scientific books and scientific institutions from twelve hundred years ago? As science looked substantially differently in the Early Middle Ages from how it looks now, it is sometimes assumed that little can be said about scientific inquiry in this period. Albeit our knowledge of early medieval intellectual culture is still limited, we are not entirely at a loss concerning how science may have been performed. In this blog post, I will introduce you to a particular element that allows us to establish scientific presence and identify the books that were used for scientific purpose – technical signs.

It is estimated that between seven and eight thousand Latin manuscripts survive from the ninth century, more than the sum of what survives from all the previous centuries. This period, known as the Carolingian Renaissance, was the first of the renaissances that Europe was to experience in the Middle Ages. It was characterized by a surge in book production, establishment of new intellectual centers, recovery of ancient learning, as well as by new scientific and scholarly works. The essential medium of knowledge production and exchange in this period was the manuscript book. Manuscript books were produced mostly in the many monasteries that covered the map of Europe at the time – more than 650 are known and all engaged in book production and study of texts to some degree.

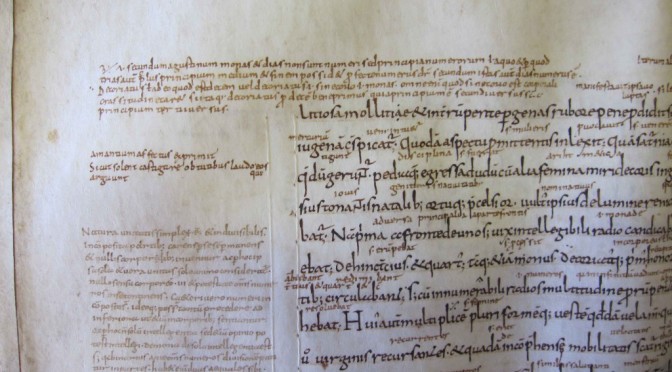

Besides writing new texts, monks-scholars also engaged in commenting on the old ones, glossing them and annotating them for their personal use or for the use of their communities. In fact, a good amount of newly produced knowledge in this period had this form. In the margins of a book, it was possible to question the authorities, disagree with them, praise them, or condemn them, to present one’s opinion alongside them, or bring several voices into harmony. Thus, the presence of marginalia is an important indicator of intellectual involvement in this period and can be used to identify scholars, scholarly institutions, intellectual projects and topics that stimulated scholarly inquiry.

Many of these marginalia were notes, similar to notes we sometimes make in books too. However, unlike us, medieval readers also used annotations in the form of symbols. They provided a system of recording information about the text that did not involve written language, and may be compared to modern use of mathematical symbols for expressing particular abstract ideas. Just as mathematical symbols, many of the early medieval technical signs served as operators – they told you what to do with a particular text passage. For example, one of the most frequent signs used in the book margins looked like a letter R. This symbol meant you should find another copy of the same text, find the same passage in that copy, and correct an error present in the first book on the basis of it.

Another sign, the nota, literally ordered you to pay attention and was used for passages that were to be internalized in the course of study. This symbol can help us today to understand the early medieval thinkers’ interests. Other signs indicated presence of quotations from other texts, passages that were problematic because of the statements they contained (such as those that disagreed with the accepted Christian doctrine), or may have been used as a tool for excerpting interesting points into a new work. Each of these operators would be easily recognized by the medieval scribes and readers, just as we today immediately recognize mathematical symbols in a text. They served as a sort of technical apparatus, not unlike modern footnotes. And just as the footnotes, presence of the technical signs in the margins of medieval books, in particular if they appear in rich layers, should alert us to the presence of a scholarly mind behind them.

The use of these technical devices is not uniform. Today, most of us use only a handful of the most common mathematical symbols, and the user of more advanced mathematical symbols can easily be identified as a specialist. Also, we make usually use of only one footnote and bibliography convention, and use it through our entire academic career. Similarly, we can see differences in use of the technical signs among the early medieval annotators. Some of the early medieval marginal signs were intended for specialized purposes or used by a particular group of scholars who studied a certain subject or represented a scholarly community in a specific region. Today, these special signs help us to identify these communities and to outline borders between regional knowledge networks, as well as to trace visiting scholars when they leave their home region. They allow us to improve our knowledge of the intellectual landscape in the Early Middle Ages and to understand the movement of the practitioners of knowledge in this period.

As an example, we can take the case of the insular peregrini, or ‘travellers’, monks and scholars coming from today’s Ireland and other areas of the British Isles, who traveled to various locations throughout Western Europe. Some may have undertaken a pilgrimage to Rome or other holy sites along an established route, hopping from monastery to monastery, sometimes staying in one of them. Others may have been interested in visiting a monastic community founded by a famous Irish missionary, a colony of their compatriots or a renowned master with whom they could study. We encounter these peregrini both in written evidence and on the basis of their characteristic insular handwriting, but in the majority of cases they remain invisible. Here is where the technical signs can help us. Just as a typical script, these insular scholars also used a specific set of marginal symbols, which are easy to distinguish from the signs that were used in the Early Middle Ages in the monasteries in France, Germany or Italy. Thus, when they marked the books they were reading, they left behind a discernible footprint, which can help us to identify them, follow their movements, and pinpoint the monasteries which provided the nodes in their continental routes.

Thanks to these insular symbols, we see that one such traveler found his way into today’s southern Bavaria in the middle of the ninth century. He spent some time in the monastery of St. Emmeram in Regensburg, only to disappear again from the radar. While he stayed at this monastery, he studiously marked one of the books present in the library there – a copy of a commentary on Jeremiah by the fourth-century church father Jerome. He stands out from the crowd on the first sight, also since he marked this book more densely than any other monk in St. Emmeram. He was an outsider, not a local man. In fact, his mode of annotation is unmatched anywhere in Bavaria. Rather, it resembles rather the signs present in several Irish books from the monastery of St. Gall in today’s Switzerland, which served as a stop-over for peregrini traveling to Italy. He may have been very well affiliated with this insular community.

This is just one example of how early medieval technical signs can aid us in tracking early medieval scholars. Naturally, they are not the only element that can help us in this endeavour. We rely on several different indicators of scholarly presence that help us to study where scholarly minds were concentrated in the Early Middle Ages, what subjects generated interest in this period, and what the local differences between scholarly communities across Western Europe were at the time. However, marginal symbols have been an underexplored field until now. In the future it is likely that they will furnish relevant data about the nature of the knowledge culture in the Early Middle Ages that will allow us to fill important gaps. Once we learn more about them, they may be an essential tool in pinpointing the scientists in the medieval crowd and identifying books that were used for scholarly purposes among the several thousands that survive from this period.

o-o-o

Evina Steinova is a PhD student in medieval studies at the Huygens ING and Utrecht University. She studies marginal annotations in the early medieval manuscript book. Her research, is part of the NWO project Marginal Scholarship: The Practice of Learning in the Early Middle Ages supervised by prof. Mariken Teeuwen. Her dissertation will be the first concise examination of the use of technical signs in the early medieval Latin West. Read more about the PhD project here and here. Evina also writes for several blogs about history and the Middle Ages.