This year, Nobel prize winning physicist Steven Weinberg published a history of Western science up to Newton: To explain the World. The Discovery of Modern Science. Weinberg was an important player in the science wars, voicing his strong intuitions that genuine science transcended history and culture against what he perceived as subversive social constructivism. Now that he has taken more than just a glance at the history of science, the result is bound to be interesting.

Historian of science Steven Shapin wrote a rather cavalier review of the book in the Wall Street Journal – titled “Why Scientists Should Not Write History”, though Shapin did not in fact deny scientists the right to write history; he only denied that this could contribute anything worthwhile to historians. The term that Shapin did not use, but which Tim Radford did in the Guardian, was “Whig history”: calling Plato “silly”, Aristotle “tedious” and Galileo “behind the times”, Weinberg’s book would commit all the sins that historians have become used to filing under the label of Whiggism.

Not everyone has been as harsh as Shapin. Or better said, some reviewers condemned Shapin for being so harsh to Weinberg. On Etherwave propaganda, Will Thomas interpreted Shapin’s view as perpetuating a mythology in which scientists are psychologically incapable of writing good history, citing plenty of cases in which scientists did not just write good history, but evidently advanced the discipline of history of science. On his blog Double Refraction, Michael Bycroft remarks – with his usual care for nuance – that the division Shapin construes between scientists and historians is “better understood as a division between historians”, and that the error in Weinberg’s book seems to be not the presentism that Shapin keeps pounding on but a violation of (a proper understanding of) the symmetry principle.

These are intelligent comments on the dispute that I recommend for their thoughtful reflections on Shapin, but they explicitly do not engage more deeply with the content of Weinberg’s book. However, when we look at the book more closely, Weinberg may sometimes surprise us, and even teach us a few lessons about the concept of Whig history.

The discovery of science

Weinberg is far from unaware of the stock controversies in the science wars, and he lays out his agenda explicitly and clearly in the introduction to his book:

“I will be coming close to the dangerous ground that is most carefully avoided by contemporary historians, of judging the past by the standards of the present. […] Some historians of science make a shibboleth of not referring to present scientific knowledge in studying the science of the past. I will instead make a point of using present knowledge to clarify past science.”

Science, Weinberg says when clarifying the subtitle of his book (‘the discovery of modern science’), was not just ‘constructed’ but actually ‘discovered’, just like agriculture was not constructed but discovered: it is the way it is because reality is the way it is, and there is really nothing more to it.

This should have sensitive contextualists shivering with terror. But not all ways of connecting past and present are the same. At least two reviewers including Shapin have noted that Weinberg calls Plato ‘silly’ and Aristotle ‘tedious’ and have interpreted this as illustrative of Whiggism or presentism; but Weinberg does so commenting on a portrayal of Aristotle’s work as “terse, compact, abrupt” – these judgments coming from Jonathan Barnes, a leading Aristotle scholar and the editor of the most recent edition of his collected works. Seen within this context, Weinberg’s defense of Aristotle as tedious but also as at least clear and serious- does not seem beyond the pale.

What is more, when we start with the presocratics – Weinberg’s history follows a well-known canon – we get this:

“It is possible that Empedocles and Anaximander used terms like ‘love’ and ‘strife’ or ‘justice’ and ‘injustice’ only as metaphors for order and disorder, in something like the way Einstein occasionally used ‘God’ as a metaphor for the unknown fundamental laws of nature. But we should not force a modern interpretation onto the pre-Socratics’ words.”

Wait, should we not? Here we were waiting for Weinberg to ride roughshod over the past and now he warns us against forcing modern interpretations upon the pre-Socratics. What does this mean?

Presentism and Anachronism

A first step towards understanding this, I suggest, is to distinguish between presentism and anachronism: between the belief that there is sufficient continuity between the past and the present to allow present knowledge to enlighten the past and the claim that things happened in that past that in fact could not have happened. Weinberg is a card-carrying presentist, but he obviously wants to take care to avoid anachronism.

Thus, when Aristotle calls the presocratics physiologi, Weinberg is quick to say that it is misleading to translate this as ‘physicists’, as does the Oxford translation edited by Barnes. Physicist, after all, is an anachronism (Weinberg does not use the term) in a time where there is not yet physics; “the early Greeks had very little in common with today’s physicists. Their theories had no bite.”

This ‘bite’ thing may curl your toes as it does mine. But it illustrates how, given Weinberg’s commitment to tracing the discovery of science in history, it is only natural for him to want to pay due regard to historical discontinuity and not to interpret just anyone as if they were doing science: the early Greek philosophers did not simply refuse to validate their theories (as scientists do); it simply could not occur to them because “they had never seen it done.” The wrongness of their theories is not due to psychological irrationality and in this sense Weinberg does not even violate the symmetry principle (though he does if that principle is not about rationality but about the explanations of true and false theories).

When discussing Aristotle’s shortcomings at length, he adds that “it would be unfair to conclude that Aristotle was stupid”. He does not want to show that Aristotle could easily have done better; he wants to illustrate “how difficult was the discovery of modern science”. There is no need to judge those who did not ‘get it yet’ for this failure, especially since they could not know what they were not getting. Repeating: “Nothing about the practice of modern science is obvious to someone who has never seen it done.”

Even if you think presentism is wrong, the vices of presentism and anachronism do not always point in the same direction – it is possible for Weinberg to comment upon everything he sees in the past through the lens of a present-day physicist while still wanting to avoid to ascribe intentions to people that they could not, for reasons of their place in time, have had. Still, Weinberg obviously differs with many historians about the question which things in the past are continuous with the present and which things are not; and even about which things existed.

Continuity, Inevitability, and the Mirror of Nature

The most troubling and challenging aspect of Weinberg’s perspective is undoubtedly the fact that he thinks that not only nature, but science itself is a thing with an independent existence, that can be discovered; that he believes he knows very well what science really is, how to recognize it; and that he is prepared to point out, in any age, who is helping this thing and who is not. Here there is something that an accusation of anachronism – something Weinberg, as we know now, wants to avoid – could hook on to: when Al-Ghazali performs an “attack on science”, does he not need to be consciously attacking science and is that even possible when he does not know what he is attacking?

There are three reasons, I believe, why Weinberg feels secure in talking about science even in periods where it has not yet been discovered. First of these is the continuities between past and present. Though Weinberg shifts a bit on the question whether premodern science is recognizable as science, a charitable reading renders his account consistent: the Islamic and medieval Christian enemies of science object to something that they could see in Aristotle and that is continuous with modern science: naturalism. “[Aristotle’s] vision of a cosmos governed by laws, even laws as ill-developed as his were, presented an image of God’s hand in chains, the same image that had so disturbed Al-Ghazali.”

A second reason is that, eventually, Weinberg believes that all relevant possible courses of history will contain science. It is more problematic to judge past philosophical systems for ethical or metaphysical ‘mistakes’ than it is to judge them for getting their science wrong and this is in part because in the latter case we can be certain that there are no genuine alternative paths to other sciences than our own, from which we might have made other judgments. In Aristotelian terms, current science already potentially exists everywhere in the past, and it is inevitable that it will be actualized sometime.

This is connected to a third reason: what science is reflects nothing but what the world is. This, I think, is the strongest reason why Weinberg believes science never to be an anachronism: in the end, science is the mirror of nature – and even if in the Middle Ages people happened not to look into this mirror yet, comparing medieval depictions of nature with what a mirror would have shown is not really anachronistic, since after all what the mirror would have shown is the world and the world existed.

Weinberg’s extreme presentism here is supported by beliefs about the causal structure of the history of science: he thinks that scientific beliefs can be reduced to the world that they are about and that this means they are highly inevitable, with a high degree of continuity between earlier and later scientific beliefs. This means that almost no application of present science to anything in history can be a genuine anachronism.

We see all these motifs in Weinberg’s judgment of Descartes. Descartes, Weinberg notes, is quite popular among philosophers (and among the French), and this is “puzzling” since he was wrong about so many things:

“He was wrong in saying that the Earth is prolate […]. He, like Aristotle, was wrong in saying that a vacuum is impossible. He was wrong in saying that light is transmitted instantaneously. He was wrong in saying that space is filled with material vortices that carry the planets around in their paths. He was wrong in saying that the pineal gland is the seat of a soul responsible for human consciousness.”

And so on. Why is it necessary to spell this out? Well, first, because Descartes is trying to find out the truth about nature and this makes his efforts potentially scientific: we are assessing not just his thinking, but to which extent it is continuous with science.

If Descartes was wrong about so many things in science, that also makes him wrong in believing his philosophy necessarily got it right about these things. This is a point against deductivism, and indirectly a point about the methods of real science: real science, by definition, is that thing that leads us to progressively closer approximation of the truth. Descartes’ philosophy hardly did that and this teaches us something about the extent to which it ought to be recognized as part of science.

This is not an all-or-nothing affair, for “even the greatest scientists make mistakes.” The point, therefore, is not a judgment of Descartes’ rationality, but that it is not aprioristic philosophy that teaches us science but the world itself.

The Teaching Machine

Weinberg provides some hints about how the world does this: in his chapter on Newton he mentions “a kind of Darwinian selection operating in the history of science”:

“We get intense pleasure when something has been successfully explained, as when Newton explained Kepler’s laws of planetary motion along with much else. The scientific theories and methods that survive are those that provide such pleasure, whether or not they fit any preexisting model of how science ought to be done.”

A somewhat puzzling analogy: if theories get to be selected on the basis of the pleasure they provide, should we not zoom in on the (possibly historically variable) kinds of things that provided pleasure to the people who got to select the theories we inherited? And if scientific theory development is Darwinian, how does it also get to be teleological? But these things aside, this is another occasion where Weinberg wants to emphasize that our teacher is, even if in some indirect way, the world itself and that by eliminating more and more unfit theories, the world acts on us like a “teaching machine”, telling us what is true science by allowing us to take pleasure in discovery.

In Newton’s work, it does. What Newton does is real science and that means that both in form and in content it manifests a lot of continuity with later scientific developments: after quoting the poet J.C. Squire’s comment on Alexander Pope’s well-known ‘Let Newton be’-epitaph, where Einstein comes to undo Newton’s light-bringing work, Weinberg adds “Do not believe it” and goes on to spell out the similarities between Newton’s and Einstein’s work.

Also, it implies that Newton’s work inevitably gets accepted; belief in Cartesianism only “delays” its reception in France. Weinberg is interested in contextual and external factors that assist in the discovery of science – after all, we have seen that this discovery is not self-evident, so its timing must have some explanations – but since science already potentially exists in its genuine form, these factors do not really get to decide what it looks like. They determine only the timing and at most the order in which things happen.

For in the end, science is not a matter of history, but of the world:

“[…] Although I cannot tell why it was Isaac Newton in late-seventeenth century England who discovered the classical laws of motion and gravitation, I think I know why these laws took the form they did. It is, very simply, because to a very good approximation the world really does obey Newton’s laws.”

Conclusion: Deconstructing Whiggism and the Role of the World

I think that from this we can draw some lessons about Whig history and say something about the kinds of things about which Weinberg may be wrong. This also reflects upon Shapin’s suggestion that what is going on here is not real history.

If Weinberg systematically makes genuine historical errors – errors of anachronism – these errors follow from his beliefs about the causal structure of history. For instance, it may be that he is wrong about the continuities between Newton and Einstein or about the inevitability of Newton’s laws or about the causal role of the world in providing us with true belief. The nature of these errors very much weakens the power of accusations of ‘Whiggism’: in the simple construction of ‘Whig history’ as a kind of history, there lies the suggestion that there is something about some attitudes to historical research, or some historical methods, that necessarily leads to a misjudgment of this past.

An example could be: the idea that past and current concepts are always easily translatable or identical. If we have no clue at all about discontinuities between past and present, then we will naturally make an awful lot of errors. But Weinberg does have a clue, and he actively seeks to avoid errors of anachronism, even correcting authoritative translations of classical Greek to that end.

Weinberg believes, like all of us, that over time some things change and some stay the same and that some change more than others. He also believes that continuities between the past and the present provide us handles on understanding the past that we should not disregard. But obviously, he has his own views about the causal structure of history and about where the continuities and discontinuities are to be found.

Thus, he believes he can be presentist because of the inevitability of science and Shapin would probably counter that he cannot, because science is much more contingent and Weinberg’s presentism leads him to commit errors of anachronism after all. (I happen to believe it is also very well possible to be a presentist contingentist, but that is another matter.) But then, this is what the debate should be about: about competing explanations for what happens in history, rather than the boundary work of the discipline of history of science.

And in this respect, there is a very good reason to take Weinberg’s book seriously. Because, though perhaps providing a reactionary rather than an innovative perspective on which episodes are important in the history of science, its explicit main thesis brings back with clarity the question of which entities are important – specifically, of what role the world that science is about plays in the historical explanation of scientific theory development.

o-o-o

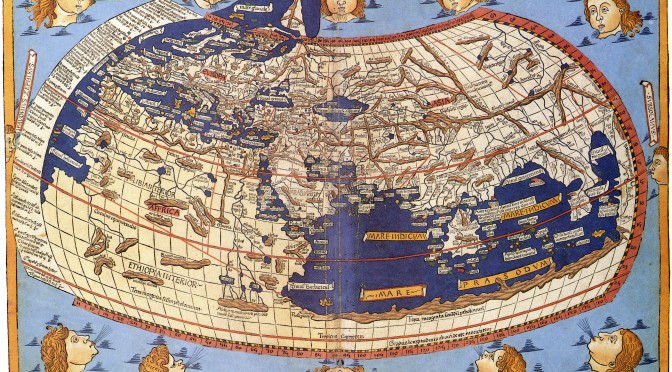

Image: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f0/Claudius_Ptolemy-_The_World.jpg