Johannes Kepler, Keppler, Khepler, Kheppler, or Keplerus was conceived on 16 May A.D. 1571, at 4.37 a.m., and was born on 27 December at 2.30 p.m., after a pregnancy lasting 224 days, 9 hours and 53 minutes. The five different ways of spelling his name are all his own, and so are the figures relating to conception, pregnancy, and birth, recorded in a horoscope which he cast for himself. The contrast between his carelessness about his name and his extreme precision about dates reflects, from the very outset, a mind to whom all ultimate reality, the essence of religion, of truth and beauty, was contained in the language of numbers.

On re-reading this opening paragraph of the Kepler chapters in Arthur Koestler’s The Sleepwalkers of 1959, I have no trouble perceiving what once made me, a 17-year old, aspiring history student with a high-school science major, read on, and on, and on. Certainly the catching, not to say gripping style. Almost certainly as well, albeit more dimly so, the virtuoso manner in which two brilliantly chosen, telling details are within the space of just three sentences being amplified into a sweeping characterization of the personality whose life and works remain from here on the author’s principal subject for some two hundred pages to come.

By now over half a century older than I was way back in 1964, I perceive in addition certain things about this paragraph that I am fairly certain failed to strike me at the time at all. There is something fishy about that sweeping characterization. Not only does it display, on some reflection, an ostensible lack of awareness that in Kepler’s time multiple name spelling was the rule rather than the exception. More important is the following. It would certainly be true to say that Kepler’s religion and his astronomical work were in striking harmony with each other, due to his very conception of a musical harmony that God had instilled in the world the geometric (definitely not the arithmetical) way. But this is hardly equivalent to stating that for Kepler “the essence of religion, of truth and beauty, was contained in the language of numbers”. And most important in this connection at all, such a leap from telling detail to all-too-neatly fitting and all-too-little-tenable generalization is (as I was to become aware later) among Koestler’s fixed features as a non-fiction writer. More than that, it is the very reason why, although he certainly was a gifted novelist and a journalist with an extraordinarily wide interest and coverage, I came in due time to regard him as, at bottom, second-rate.

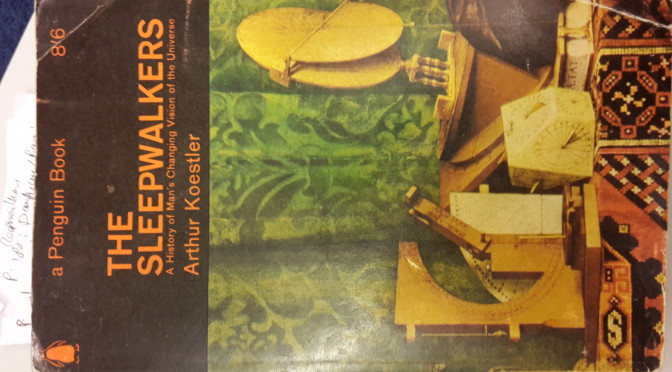

All of which is to say that over the years I have become a good deal more critical about the first book on the history of science that I ever encountered and devoured than when I first read it in the best-selling Penguin edition of 1964. And yet, on re-reading it for the hoped-for benefit of ‘Shells & Pebbles’ I am struck by how much I now find to have picked up at the time from The Sleepwalkers to the extent of becoming fixtures of my own writings without any remaining awareness that that is where I encountered them first. In other words, the book left a lasting imprint, and in what follows I shall give a few examples of how, and in what respects, it did.

But let me first outline what the book is about. Its much too spacious subtitle is ‘A History of Man’s Changing Vision of the Universe’. The introductory Part hurries the reader in just over a hundred pages of potted history from Thales to Copernicus, after which the pace slackens considerably, only to be regained near the end, where a post-Galileo follow-up brings the story to Newton in just over ten pages, followed in its turn by a final conclusion, a bibliography, and numerous endnotes. In between these relatively brief opening and closing portions the book consists of lengthy accounts (close to 400 pages together) of the lives and achievements of its three main persons: Copernicus (‘The Timid Canon’), Kepler, and Galileo, with a much shorter sketch of Tycho worked into the story as well.

Why the title? What turned Copernicus, Kepler, Tycho, and Galileo, but Kepler above all, into (of all things) sleepwalkers? In part the title is meant to convey the idea that there is much more to the creative act than can be accounted for in a rationally reconstructible, linear sort of step-by-step account. More than that, the creative scientist, so Koestler argues using Kepler’s discovery of the elliptic shape of planetary orbits as his prime witness, literally does not know what he is doing while he is doing it. But the principal theme of the book is the related idea that Science and Faith (the capitals are Koestler’s) could, and should, have remained one and the same. Indeed, the truest sleepwalking capacity is given to those in whom Science and Faith (of a mystic kind overall) have not attained, or been affected by, their disastrous rift — a gradual falling apart that, so Koestler argues, first occurred with Galileo’s trial in 1633.

If I remember correctly, I mostly ignored the book’s main themes, gripped as I was as a youngster by the catching, imaginatively told story. How imaginative (but now taken in the negative connotation of the word) I did not care to find out. There is some solace here for us teachers — give a youngster a book with a pretty obviously untenable or at least way overdone message, and she or he may well prove capable, not only of picking up its saner aspects, but also of being inspired by that very message to the point of turning in due time toward more solid scholarship and more responsible grand visions.

Many more stylistic gems than the one I opened this piece with are strewn over the book, most often meant to express an at times quite striking psychological insight of a kind that betrays the novelist. People love to read about people, more in particular about special people, admirable people. People also like to read about science, as well as about history. We, historians of science, deal with all of this: with people; with special, often even admirable people; with science, and with its history — why, then, are we so habitually failing those numerous potential readers of ours who do harbor these quite legitimate needs? If we do not at least once in our career write up our results in a way accessible beyond the profession, then others wiIl do it for us. Journalists in particular do it for us, and Arthur Koestler was by no means the worst journalist to give it a try, even if he himself was in addition guided by those other, more personally colored motives of his. Definitely surpassing much then and now current work in broadly accessible history of science writing, Koestler had quite a good grasp of the literature. He even went at often considerable length and depth into numerous, remarkably multi-lingual sources (not only the Collected Works of his main persons but also, for instance, the entire file of Kepler’s mother’s witch trial). The problem with his treatment is not so much a lack of scholarly underpinning (at least as considered from the viewpoint of the late 1950s when he wrote the book) but rather the extent to which his preconceived views tended to disfigure too many of his historical interpretations.

Even so, Koestler’s preconceived views sometimes made his historical outlook remarkably acute. Compare, for instance, how the amateur Koestler in 1959 and the professional Maurice Finocchiaro in 2007 analyzed certain well-known events in Galileo’s dealings with the Church authorities. Unlike Finocchiaro, Koestler is not taken in for a moment by the effort undertaken by the Inquisition in the aftermath of the trial to portray all previous events as leading up to the final condemnation. He thus perceived what many students of the ‘Galileo affair’ still overlook, to wit, that in 1615 the Inquisition had dismissed all complaints filed by the lower Florentine clergy against Galileo’s Letter to the Grand Duchess. In a related vein, Finocchiaro does not take seriously what the Grand Duke’s ambassador in Rome wrote in 1615 to his master, on the grounds that Guicciardini’s messages display his lack of understanding of the scholarly matters at hand. That may be so, and yet Koestler as a politically experienced man-of-the-world understood far better that diplomats are as a rule very astute at sniffing an atmosphere, an intellectual atmosphere definitely included. Therefore Koestler quite rightly takes up as a vital element in his interpretation of what happened in 1615 the key message that Guicciardini insisted on in his reports to Cosimo II —a message that came down to ‘please call Galileo back from Rome before, in seeking to enforce this Copernican stuff upon the Vatican, he uses the opportunity to break even more porcelain’. To be sure, I cannot possibly go along with Koestler’s unreserved ‘first rift in the Science and Faith harmony’ interpretation of Galileo’s tribulations, yet from when I first read the book onward I have adopted numerous significant details and interpretations in his account thereof, most of all his view (powerfully reinforced by Guicciardini’s pertinent reports) that over almost the entire affair it was Galileo, not the Church, who was on the offensive. Also, I still concur with Koestler’s view that the scandal of the trial need never have happened, even though to Koestler this means that the rift between Science and Faith need, and should, not have occurred at all, whereas I regard the rift as inevitable on the long term, albeit not indeed on the short term of the 1630s.

Among further things that I have now found to have adopted from The Sleepwalkers are the need to make explicit one’s own inevitable bias when addressing Galileo’s trial and all that led to it. Also, so I now find, this book is where I first encountered the very notion of The Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, that has come to mark just about all my later writings.

As it happens, I am hardly the only person still to feel a need to deal with Koestler’s Sleepwalkers decades after its first appearance. In his Retrying Galileo of 2007, a most useful book overall, Finocchiaro has included a not particularly fair chapter on The Sleepwalkers. In quite another vein, Owen Gingerich made an ironic bow to Koestler. He did so by giving his own exhaustive study of all surviving copies of Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus and the plethora of extensive marginal comments he encountered in those copies the title The Book That Nobody Read — a most effective demonstration of how deeply mistaken Koestler was in his claim, made in those very words, that Copernicus’ book was an all-time bad-seller. And let me conclude with an example of The Sleepwalkers’ lasting effect in quite another vein again. In his chapter on Copernicus Koestler discusses at some length the difficulties that Copernicus, the ‘timid canon’, had with his former colleague and now titular head, a humanist bishop by the name of Johannes Dantiscus (literally ‘from Danzig’). Koestler memorably characterizes the man as follows: “During his ambassadorial years, Dantiscus’ main interests had been poetry, women, and the company of learned men, apparently in that order’. In 1974 a great, radically feminist Dutch novelist entitled her collected essays Poëzie, jongens en het gezelschap van geleerde vrouwen. Faithfully translated as ‘Poetry, boys, and the company of learned women’, this is a title that Koestler (who entertained rather primitive ideas about what women are good for) would probably have enjoyed a good deal less than I did when I encountered the title and recognized at once what particular line in what particular book this Dutch novelist was so wittily alluding to.