In case of an emergency you call the emergency hotline, and help arrives quickly. This seems so straightforward that one almost forgets it requires a lot of coordination and organization. At the turn of the twentieth century the organizational structure behind emergency medicine developed significantly. Especially fundamental was the introduction of triage during the First World War, which decided the order of treatment on the basis of the urgency of the wound.[1] This medical decision-model replaced the traditional way of working that relied on the rank of the patient, and is still at the core of emergency medicine today. How emergency medicine was organized before this change came about, I will elucidate through a unique historical source: a census, published shortly before the triage was introduced. This will shed light on the very muddy and opaque organizational structure of emergency medicine of early twentieth century

The Census

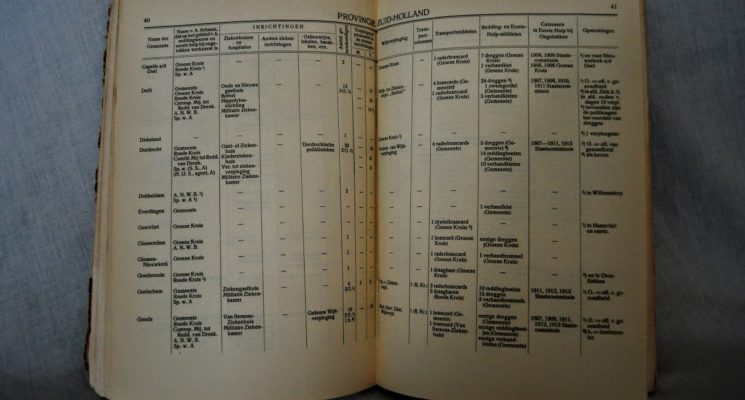

The need for more organization rose after shipwrecks such as the famous 1907 disaster in Berlin. Help did not arrive in time so that 128 people died due to a lack of medical coordination and training.[2] In order to prevent such wrongs in the Netherlands, a census of all emergency medicine organizations had to improve coordination. The initiative for the census came from The Koninklijke Bond voor Reddingwezen en Eerste Hulp bij Ongelukken (lit. Royal society for First Aid), Het Oranje Kruis (Orange Cross) and the Nederlandsche Roode Kruis (Red Cross). These organizations lobbied and were eventually granted the ministerial approval and a grant for research.[3] The census contains an extremely detailed description of every organization and all medical staff who were affiliated with emergency medicine within every municipality in the Netherlands between 1911 and 1915. The census is so thorough that it even accounts for all equipment, from (in)complete contents of first-aid kits and number of stretches, to life vests and vehicles.

The Authors

Cornelis Johannes Mijnlieff was a secretary of the board of directors of the Oranje Kruis when he was approached by the Ministry of Domestic affairs to map all organizations that had anything to do with first aid. Mijnlieff was a pioneer in the field of emergency medicine. Although it was not considered a separate discipline at the time, he was part of a group of pioneers, under the banner of Prince Hendrik, which set out to fundamentally change the way emergency medicine was organized in the Netherlands. In his dissertation from 1905 Mijnlieff argued for the necessity of this reorganization because the quality of the Dutch organization was far behind other European countries. Already in 1892 Mijnlieff had been introduced in Vienna to the Wiener Freiwillige Rettungsgesellschafft.[4] Here he noticed the superior level of organization of emergency medicine, especially in comparison to primitive organizational level in Amsterdam. Intrigued by the experiences in Austria and shocked by the primitive conditions in the Netherlands, Mijnlieff wrote his dissertation to contribute to the improvement of the organizational structure of Dutch emergency medicine.[5]

The Organizational Structure

Reading the census today, it becomes clear how whimsical the underlying organizational structure was. All in all, about fifty different organizations of various religious, commercial or public nature were active across The Netherlands, without any central coordination or much communication.[6] Within these fifty organizations three larger organization types existed that where the focal point of emergency medicine in the area, where equipment was stored and medical expertise was available:

- De Kruisverenigingen ( Organizations of the Cross), which were based on the strict religious separations in Dutch society, although they tried to operate ‘neutrally’.[7]

- Gemeentelijke Geneeskundige Dienst ( Municipal Health Department) were active on a municipiality basis. [8]

- De Maatschappij tot Redding van Drenkelingen ( Society for the aid of the drowning).[9]

The organizational focus of the census leaves many important actors out of the story. While organizations varied widely per municipality and religion, the police force turned out to be vital for communication and organization. This was due to the fact that they often had the only telephones in the region in their office. [10] The role of the police becomes clear in Mijnlieffs’ dissertation, though it is odd that they are not mentioned at all in the census. In his dissertation he also distinguishes between three different types of people under the flag of emergency medicine: next to medical and non-medical professionals, bystanders played a role as well. Invisible in the census, Mijnlieff stressed that bystanders or ‘Samaritans’ as he addressed them, played a vital part in emergency medicine. The bystanders were usually lay men who happened to be at the scene of the trauma.

Mijnlieff, for this reason, was a strong advocate for educating lay people in emergency medicine. But the role of laymen in the professionalizing practice of medicine was not warmly welcomed by all. In the nineteenth century some felt it was a faux pas to have common folk practice any kind of medicine. It would go against the hard fought rights of performing medical procedures which was formalized in the law of Thorbecke in 1865.[11] Mijnlieff, however, payed much attention to standardizing education in both his census and his dissertation. In the end urgency for care and the proximity of possible caregivers trumped the rigorous division of religion and social class. Many agreed with Mijnlieffs’position, including Prince Hendrik and other political figures. Their combined influence made it possible for the education of lay people to be structurally organized and allow the Oranje Kruis perform its current function in today’s’ society.[12]

Conclusion

All these organizations and people worked under the flag of emergency medicine, though it was not their only or even main activity. The organizational structure differs from municipality to municipality, and from religion to religion. This made it opaque and very difficult to wade through all these organizations and people and to see the organizational structure.

The census does remain to give us a unique insight in which organizations were active in which region. It was a near impossible task to be as precise as the census is and the neutrality of the authors regarding the organizations can be seen by the sheer diversity in type of organization is amendable. In this the census does exactly what a census should do, to show were something is during a given period of time. However, the census is therefore limited in what it can show. Not everyone who was active in emergency medicine was shown. The Samaritans and the police force were invisible, as are the organizational and communicational structures, if there were any.

Mijnlieff would continue to pioneer within this emerging specialty by publishing and organizing conferences and much more. He would become a key player in furthering the improvement of the organizational structure. If Mijnlieff would only know that we now call emergency services using a mobile phone almost everywhere and within fifteen minutes help would arrive. He would be ecstatic.

[1] Iserson KV, Moskop JC (March 2007). “Triage in medicine, part I: Concept, history, and types”. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 49 (3): 275–81

[2] Kerkhoff, Toon, and Joshua Martina. “Advies Aan De Regering: Staatscommissies in Nederland Tussen 1814 En 1970*.” Beleid En Maatschappij 42.2 (2015): 79-101. ResearchGate. Jan. 2015. Web. 15 Jan. 2017.

[3] Mijnlieff, C.J, and A. A. J. Quanjer. “Voorwoord” Gegevens Omtrent De in Nederland Bestaande Organisaties En Regelingen, En Omtrent Het Aanwezige Personeel En Materieel Op Het Gebied Van Het Reddingwezen En Eerste Hulp Bij Ongelukken. Rotterdam: W.L. & J. Brusse, 1915.

[4] (Lit,) Vienna Voluntary Rescue Company

[6] Blokker, Bas. “Bij Het 225-jarig Bestaan Van De Maatschappij Tot Redding Van Drenkelingen.” NRC (30 Dec. 1992): n. pag. Nrc.nl. 30 Dec. 1992. Web. 27 Oct. 2016. <https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/1992/12/30/bij-het-225-jarig-bestaan-van-de-maatschappij-tot-7167895-a624098>.

[7]Huisman, Frank. “Verpleging en verzorging: wiens geschiedenis?.”Gewina/TGGNWT 27.2 (2004): 120-125.

[8] Gras, Th, and Gerrit Rottink. De Broeders Van De Breukendienst: 100 Jaar Eerste Hulp En Ziekenvervoer Door De G.G.D. Amsterdam, 1908-2008. Zaltbommel: Aprilis, 2008.

[9] Blokker, Bas. “Bij Het 225-jarig Bestaan Van De Maatschappij Tot Redding Van Drenkelingen.” NRC (30 Dec. 1992)

[10] Gras, Th, and Gerrit Rottink. De Broeders Van De Breukendienst: 100 Jaar Eerste Hulp En Ziekenvervoer Door De G.G.D. Amsterdam, 1908-2008. Zaltbommel: Aprilis, 2008.

[11] Deneweth, Heidi, and Patrick Wallis. “Should we call for a doctor? Households, consumption and the development of medical care in the Netherlands, 1650–1900.” this issue (2014).

[12] Het Oranje Kruis. “Over.” Het Oranje Kruis. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Feb. 2017. <http://www.hetoranjekruis.nl/over/>.