Prize contests are not a medium many people would associate with science nowadays. Academic papers and books produced in the context of universities are the norm these days. Yet, this has not always been the case: historically, universities were primarily training grounds for generations of lawyers, theologians and doctors. A lot of interesting research went on outside academia, in the many scientific societies of early modern Europe. These scientific societies organized numerous prize contests on a wide array of topics. However, in the process of doing research I encountered all kinds of curious entries and mishaps. In a somewhat anecdotal fashion, I will highlight some of the more curious outgrowths of this system of knowledge production.

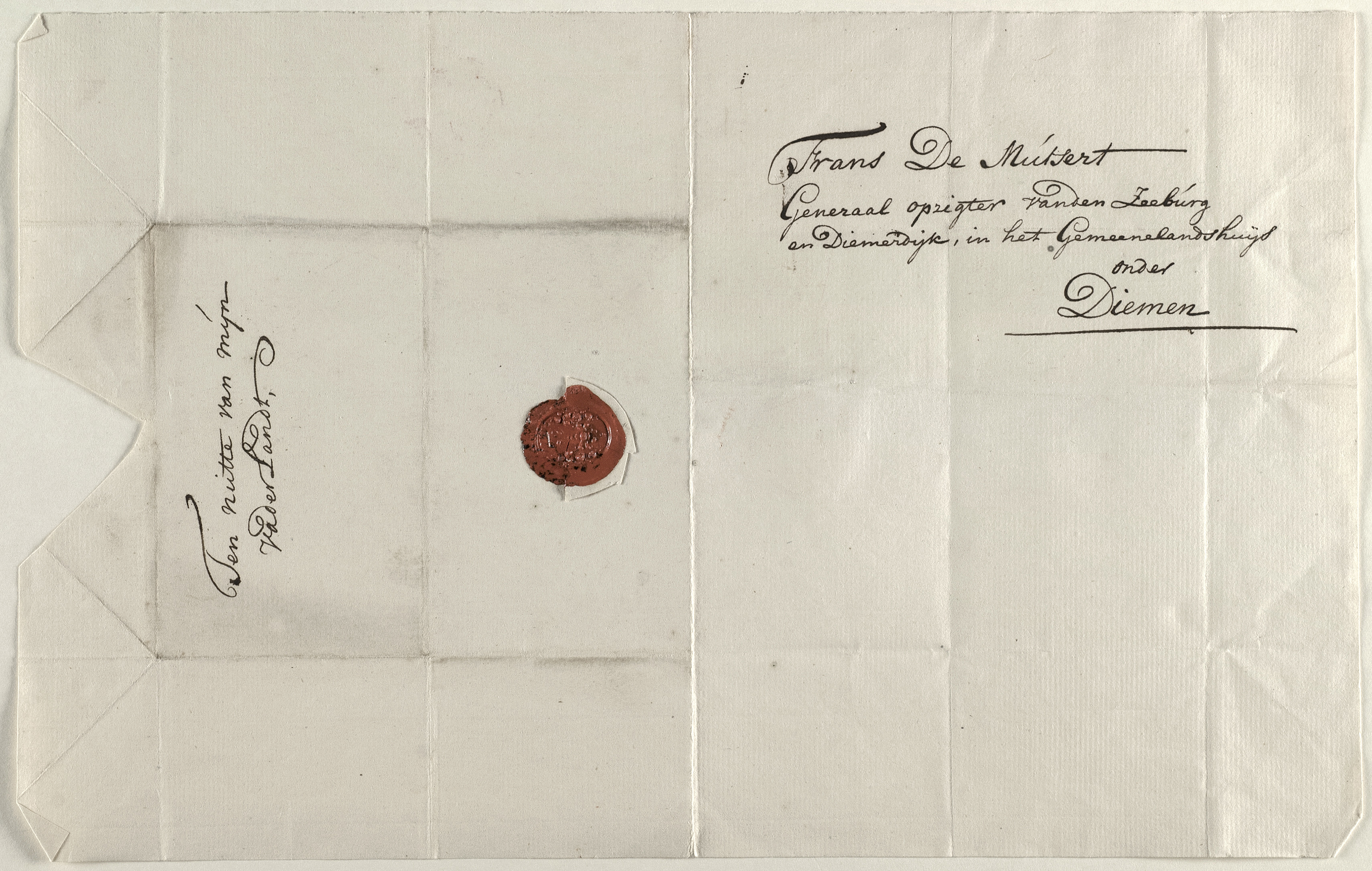

In my master’s thesis I focused on two of those societies in the Dutch Republic/the Netherlands: the Provincial Utrecht Society (Provinciaal Utrechts Genootschap, PUG), and the Dutch Society for the Sciences (Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen, HMW) based in Haarlem. These societies facilitated knowledge production by organizing prize contests, in which anybody was free to participate in exchange for prizes, awarded by a jury of reputable scholars, who reviewed the submissions blindly (see cover image: hidden nametag on prize contribution). My main question was which notions of ‘good science’ were present in the jury reports within these societies. First, I will briefly introduce the two scientific societies I studied, and then present some of the cases, which illustrate the virtues and vices of knowledge production in the 19th century.

The rise of scientific societies

The emergence of a Dutch world of societies took place in the second half of the eighteenth century, more than a century after illustrious rivals like the Académie Française (1635) or the Royal Society (1660). [1] After the founding of the HMW in 1752, a number of other national societies as well as a whole host of smaller societies came into existence. The HMW was followed by the Zeeuwsche Genootschap van Wetenschappen in 1765, the Bataafsch Genootschap der Proefondervindelijke Wijsbegeerte in 1769, the Provinciaal Utrechtsch Genootschap voor Kunsten en Wetenschappen in 1773, the Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen (operating from colonial Batavia) in 1778, and Teylers Genootschap, also in 1778. In addition to these societies which had members from all over the Netherlands, there were many smaller locally oriented societies, which often connected the middle class citizens or provincial towns – doctors, lawyers, etc. – who had an interest in science. These local societies generally did not engage in active research, but filled their meetings mainly with lectures and demonstrations. The national societies were more interested in the acquisition of (useful) knowledge. Why did this torrent of societies suddenly appear after 1750? The most important reason was the rise of a new ideal of citizenship in the Dutch Republic, in which one could display civic virtue by engaging in useful science, because this halted the material and moral decay of the nation.

The well-meaning amateur

Being useful to the nation in this way was not only possible for university scholars, but amateurs could also contribute, if they had enough time on their hands. The announcements for prize contests were published widely, so anyone who wished could participate. Although the share of ‘professional’ scholars was substantial, the number of ‘outsiders’ participating in the contests was quite large. J. Konijnenburg, a minister and professor at the Remonstrant seminary in Amsterdam is one of the most fascinating examples of such a well-meaning amateur. He wrote on a wide range of topics and participated in no less than ten contests of the prestigious Dutch Society for the Sciences (HMW) between 1813 and 1830.

The ten essays concerned bird migration (which he won), the qualities of lump lime vs. shell lime, the value of translating classical poetry in Dutch (again successfully), the (dis)advantages of snow and frost for agriculture, the professional ethos of the historian, the introduction of exotic plants in the Netherlands, the difference between a ‘pragmatic’ history and a philosophical or political treatise, the matter of bird migration (once again), as well as of migrating fish, and the unique breeding procedure of the cuckoo. Perhaps not surprisingly, most of his entries were rejected because they showed not nearly enough familiarity with the subject, but Konijnenburg also won a number of medals. He was maybe exceptional in the unusual range of subjects he participated in, but figures like him were not uncommon in the earlier decades of the scientific societies.

Peer review & plagiarism

In reviewing the prize contest entries, the reviewers sometimes struggled to find clear criteria but also insisted that the contestants handed in serious and original work.

One of the open questions that the members of scientific societies struggled with, was who exactly the public was. Were the prize essays written for a small public of learned men, or could they also provide enlightenment to the general public? In medical questions, for instance, was it permissible to add a moral exhortation to the description of the disease? One entry for the 1782 contest included long moral digressions on the excessive consumption of food or alcohol as a cause of nervous illness. The reviewers J. Veirac and L. Bicker did not appreciate this. Bicker, a Rotterdam physician, judged one of the entries as quite excellent, although “in general it is rather verbose and contains numerous unnecessary moral and spectatorial digressions.” [2] Veirac agreed that these lectures did not belong in medical treatises but also, inconsistently, criticized the entry for talking too much about excessive food and alcohol consumption, but not enough about divorce as a moral cause for nervous illness. The case shows that, as Bicker wrote in a letter to the PUG, that it was hard to participate in contests like this without knowing whether the PUG intended the entries to educate the public in “what the causes of their nervous illnesses were and how to prevent them.” [3]

This particular entry is also remarkable for another reason. Bicker’s complaint about the digressions in the entry cited above was a rather striking comment, since Bicker was commenting here on his own entry! He had written one of the submissions and had subsequently been commissioned by the PUG to review them, a commission which he should have refused according to the rules, but apparently did not in the hopes of increasing his chances of a medal. Given this curious fact, we should maybe take his self-castigation with a grain of salt, added only to make the feedback appear more convincing. While it was controversial who science was for, it was clearer that taking shortcuts to scholarly distinction was not appreciated, as some further examples will make clear.

While this case of a reviewer reviewing his own work was obviously an exception, plagiarism was a more common issue. Within the HMW it happened every now and then that a contestant tried to win a prize by submitting other people’s work, or recycling their own work. An 1821 entry by H. Antheunis on oysters turned out to be copied from the Dictionnaire d’histoire naturelle. HMW director Van Marum almost decided to publicly shame the author by making his name known to the public as Plagiaris. [4] Even the great chemist Justus Liebig was chided when he sent in an entry that was basically an excerpt from his own earlier work. [5]

Within the PUG in 1831, S.J. Galama did something similar, by submitting an essay that was based on an earlier entry for the HMW. [6] In a meteorological question of 1837, Van Marum thought it wise, therefore, to add that he wanted to see citations for all places where the contestants made use of existing scientific works. [7] It was paramount to combat the inadmissible practice of what one reviewer called ‘letterdieverij’. [8]

In conclusion, nineteenth-century knowledge production has some noticeable similarities as well as differences to contemporary practices. The most striking difference is the active participation of amateurs in the scientific societies, motivated as they were by the moral imperative to be useful to the country. During the nineteenth century this model gradually became less sustainable. The growing complexity of science and the increasing number of university-educated scientists who did their research within university institutions made the prize contests increasingly marginal. At the same time, not everything has changed. The examples of fraud and plagiarism cited here show that trying to beat the peer review system and taking shortcuts to scholarly distinction are unfortunately still with us today.

Notes

[1] Membership of the French Academy was much more limited than within the Dutch societies, however. See W.W. Mijnhardt, “Het Nederlandse genootschap in de achttiende en vroege negentiende eeuw”, De negentiende eeuw 7 (1983), 78.

[2] Het Utrechts Archief, PUG archive, inv. no. 242.Original quote: “over ‘t geheel is het te wijdloopig geschreven, heeft veele onnoodige moraale en spectoriaale uitweidingen.”

[3] HUA, PUG, inv. no. 242,letter Bicker to PUG, 12-12-1782. Original quote: “Eindelijkbehoor ik te weeten of de vraag alleen is ingerigt ter instructie der medici,dan te gelijk om alle onze landgenooten te leeren welke de oorzaaken van hunnezenuwziekten zijn en hoe zij die kunnen voorkomen.”

[4] Noord-Hollands Archief, HMWarchive, inv. no. 420, question no. 232.

[5] According to De Bruijn thereviewers made a mistake here in dismissing a famous figure like Liebig (DeBruijn, 209). However, judging by the reviews, the reviewers were quite awarethat Liebig was the writer and they held him in high esteem based on hisearlier work, which is why they saw this act of self-plagiarism asdisappointing and insulting to the society. Said Reinwardt: “het moet ook ten hoogsten onze verontwaardiging opwekken,door de minagting, die de schrijver met hetzelve aan de Maatschappij te hebbendurven aanbieden, jegens dezelve heeft aan den dag gelegd, en dat wel eenschrijver die boven zoo vele anderen aldoor getoond heeft in staat te zijn ditonderwerp grondig te behandelen en die aan het scheikundig publiek bij anderegelegenheden onderscheidene schoone, doorwrochte en hoogstbelangrijkeverhandeligen geschonken heeft.” Van Breda made the same point: did Liebig really thinkwe would not recognize this for what it is? Dutch chemists might not be famousin Europe, but they were aware of the work of Liebig. See NHA, HWM, inv. nr.429, question nr. 321.

[6] Reviewer Pennink caught himred-handed, however. UA, PUG, inv. nr. 249.

[7] De Bruijn, Inventaris van de prijsvragen,260. Original quote: “Men verlangt van al hetgeen men ter beantwoordingbijbrengt, de schriften te zien aangehaald, waaruit men het bijgebragteontleend heeft, of waarop hetzelve gegrond is.”

[8] UA, PUG, inv. nr. 243. Letter dated 25-01-1820.