By Constance Sommerey

I like fern. I like the way fern unfolds itself, its elegance and its seemingly everlasting greenness. I really never gave this character trait of mine much thought. After all, it’s just fern. Yet, two years ago, something changed.

In 2011, I visited the botanical garden in Cleveland, Ohio. When strolling through the section devoted to fern, my eyes fell on one of those little information cards you can often find stuck into the soil in didactically responsible botanical gardens. This card revealed something astonishing: Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) suffered from pteridophobia (‘pteris’ is Greek for fern. From Greek ‘pteron’ meaning feather). Freud, who encountered the most disturbing patient stories on a daily basis, was morbidly afraid of fern!

Pteridophobia

Freud’s pteridophobia offered the perfect starting point for my endeavor. At least so I thought. As the founding father of psychoanalysis, I assumed that Freud would have written about his arguably unusual fear. Yet, my search yielded no results. It seems as if Freud himself never explicitly addressed his fear and its possible causes. Neither could I find any reference concerning Freud’s pteridophobia in the many biographies that have been written on him. There seems to be no reliable source that actually confirms Freud was afraid of fern. Had I known about the uncertainty that surrounds Freud’s pteridophobia, I certainly would have approached an employee of the botanical garden to seek further information. I have to admit that I simply trusted the little information plate. The only piece of information I could find stems from an article on cracked.com which, in an attempt at Freudian analysis, speculates about a “childhood episode involving fern and his [Freud’s] penis”.[2] This is a rather scanty harvest, considering the hardly convincing analysis and the lack of references. Could it be that my interesting finding, Freud’s fear of fern, turns out to be an urban legend? Could it be that there is no such thing as pteridophobia at all?

The next step in my quest was to find out more about pteridophobia in general. When were the first cases described? What are the causes? Is pteridophobia a real phobia or only a figment of someone’s imagination? The Encyclopedia of Phobias, Fears and Anxieties does refer to botanophobia, the fear of plants, but does not mention pteridophobia.[3] On the countless phobia-related internet sites on the other hand, pteridophobia pops up now and again. I could furthermore find a blog entry which triggered actual pteridophobes to share their fear with fellow sufferers. The fear of fern seems to exist and it therefore might have existed in the past. Yet, I was still none the wiser.

I was almost ready to give up. There are contemporary cases of pteridophobia, yet no one ever bothered to write about it and whether Freud suffered from it or not remains a mystery. Or could it be that I started my quest with the wrong finding? Maybe it’s not Freud’s fear of fern but my own love for fern that could be a more fruitful starting point? This time I was more successful. My attention was again drawn to the 19th century, yet this time the location was not Freud’s Austria but Victorian Britain. For the 19th century not only spawned Freud’s alleged fear of fern, it also spawned a Victorian movement called pteridomania; the ‘fern-craze’.

Pteridomania

Between 1830 and 1890, Victorian households developed a downright obsession with fern. It was Charles Kingsley (1819-1875) who first coined the term as early as 1855 in his book Glaucus:

“Your daughters, perhaps, have been seized with the prevailing ‘Pteridomania’, and are collecting and buying ferns, with Ward’s cases wherein to keep them (for which you have to pay), and wrangling over unpronounceable names of species (which seem different in each new Fern-book that they buy), till the Pteridomania seems to be somewhat of a bore: and yet you cannot deny that they find enjoyment in it, and are more active, more cheerful, more self-forgetful over it, than they would have been over novels and gossip, crochet and Berlin-wool. At least you will confess that the abomination of “Fancy-work” – that standing cloak for dreamy idleness (not to mention the injury which it does to poor starving needlewomen) – has all but vanished from your drawing-room since the “Lady-ferns” and “Venus’s hair” appeared; and that you could not help yourself looking now and then at the said “Venus’s hair”, and agreeing that Nature’s real beauties were somewhat superior to the ghastly woollen caricatures which they had superseded.”[4]

Fern became the new standard of beauty inside the home. Instead of man-made ‘fancy-work’, nature’s own creation found a place in the daughters’ hearts. Not only the daughters were enchanted, also Kingsley himself acknowledged that ‘Nature’s real beauties’ were superior to previous artifacts of interior design.

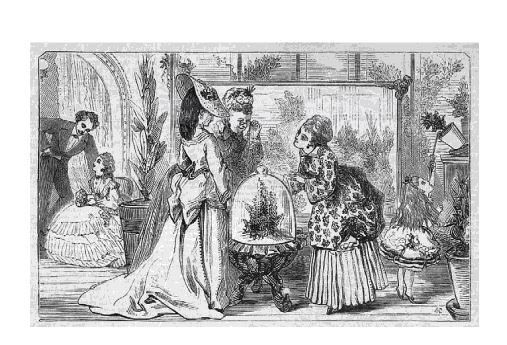

The ‘fern craze’, however, did not stop with relocating nature to the living room. The years after Kingsley’s observations brought about a fern-centered ornamental culture. ‘Fancy-work’ became predominantly occupied with the fern motif. Fern literally materialized onto everything that could be bought. Fern images could be found on glass and on wood, on windows and cloths, on paintings and gravestones. It seems that, during 19th century Victorian times, fern was everywhere.

![Victorian fern decorated iron cast seat.[5]](https://i0.wp.com/www.shellsandpebbles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/fern-iron-cast-seat.jpg?resize=450%2C274)

In the 1830s, she argues, many factors came together that changed the fate of fern. Botany was no longer confined to botanists. The love for keeping plants began to seep through to the lower classes. Decorating your house with plants and plant ornaments became seen as ‘good taste’; an essential element in Victorian times. Fern proved the perfect plant: it was native to Britain, it could grow and flourish in dark living rooms and its lush and green Gestalt carried a certain degree of mysticism.

The scholarship on pteridomania provides an intriguing overview of this fascinating fern-obsessed time. My own pteridophilia apparently has a place in history. None of these authors, however, points out the other side of the coin. My initial finding, Freud’s pteridophobia, is not mentioned once.

Still, there are pteridophobes today and Freud developed his alleged fear in a time in which seemingly every Brit was crazy about fern. What is the correlation between pteridomania and pteridophobia? There seems to be something ‘uncanny’, to stick to Freudian terms, about fern that attracts some and disturbs others.

This story, however, still needs to be written. For now, one thing becomes clear: since the 19th century, there has been something about fern.

o-o-o

Constance Sommerey is an editor of Shells&Pebbles and a PhD candidate at the Faculty for Arts and Social Sciences at MaastrichtUniversity. In her dissertation, she investigates Ernst Haeckel’s (1834-1919) rhetoric of evolution and its appropriation in German biology school books (1918-1960).

[1] With special thanks to Julie Mason. The photo was retrieved June 6th 2013 from her website: http://www.juliemmason.com/2011/05/day-140-pteridophobia/

[2] I. Cheesman, 6 Absurd Phobias (And The People Who Actually Have Them). Cracked.com 2009. http://www.cracked.com/article_16472_6-absurd-phobias-and-people-who-actually-have-them.html (4 June 2013)

[3] R.M. Doctor, A.P. Kahn, C. Adamec, The Encyclopedia of Phobias, Fears, and Anxieties (New York 2009)

[4] C. Kingsley, Glaucus; or, the wonders of the shore (Cambridge 1855) 4-5.

[5] Both pictures were taken from P.D.A. Boyd, Ferns and Pteridomania in Victorian Scotland. The Scottish Garden Winter 2005 24-29. The article and more pictures of fern-inspired artifacts can be found on:http://www.peterboyd.com/pteridomania2.htm

[6] Cf. D.E. Allen, The Victorian Fern Craze: A History of Pteridomania (London 1969); P.D.A. Boyd, Pteridomania – the Victorian passion for ferns Antique Collecting 28:6 (1993) 9-12; S. Whittingham, Fern Fever. The Story of Pteridomania (London 2012).