Once in a while, the archives offer moments of exhilaration, when the sources depict something surprising, unusual, or simply strange. Sometimes these feelings can stem from finding some familiarity where you didn’t expect it to exist. That was the case when I encountered the set of drawings above in a student scrapbook from 1903 at Bryn Mawr College Archives in the US. At the turn of the 20th century, scrapbooks were a way to collect memories of college, especially for female students. They usually contained ticket stubs, programs of plays performed at the college, news clippings, invitations, call cards, and notes from friends.1

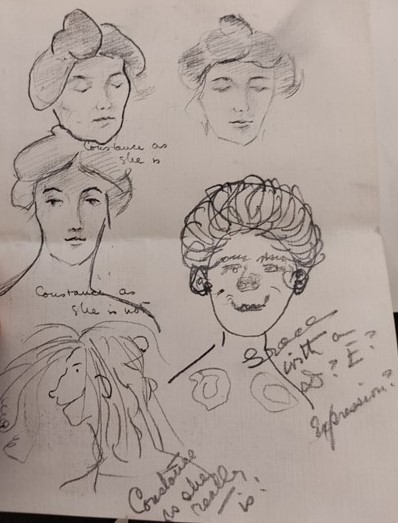

When I opened the scrapbook of Edith Dabney, who graduated from Bryn Mawr in 1903, my attention was drawn to a small piece of paper with five female figures drawn on it. Drawings were a common addition to scrapbooks and students often drew portraits of each other, but the texts associated with the pictures amazed me: “Constance as she is,” “Constance as she is not,” and ”Constance as she really is.”2 The drawing looks like a meme! In the 21st-century social media vernacular, memes are quickly spreading and often humorous ideas, condensed into pictures or videos, that are easily recognized, consumed, and shared with others.3 This particular drawing in the archives gave me a moment of familiarity, as it reminded me of one particular type of meme.

Before diving deeper into the drawing, however, it is worth explaining briefly what I was doing in a small liberal arts college in the suburbs of Philadelphia. In my doctoral dissertation, I research the construction of gender and race through the discourse on civilization in elite single-sex colleges between 1890 and 1914 in the US.4 To put it more simply, I try to make sense of why some colleges focused on educating only men or only women, as well as how this kind of gendered divide was also linked to contemporary ideas of race and assumed racial progress. I have approached these questions by looking at the scrapbooks described above, as well as student correspondence, and speeches from educational experts, among others.

One particular archival trip led me to the drawing above. It raises a couple of questions: how to interpret the drawing as a source, and what does it tell us about broader narratives of women’s higher education at the turn of the 20th century? Also, why do I compare it to a meme? To answer this last question first, it was the language of the drawing that piqued my fancy. From our 21st-century perspective, anyone familiar with social media and the world of memes can recognize the parlance of the texts attached to the drawing. It is one that toys with different perspectives of a person or a phenomenon, and its modern version consists often of the view of friends, society, parents, and one’s own, as well as some kind of depiction of an assumed humorous reality. The fun of the meme consists of the contradictions between these differing viewpoints that still somehow summarizes different qualities of the subject, as showcased by the example below.

The meme about what historians do consists of various perspectives on what it means to be a historian. To friends, being a historian might come across as endless time scrolling on our screens, occasionally writing a sentence here and there. The mother’s perspective reflects, in my view, a somewhat more sophisticated aspiration of being surrounded by works of wisdom and contributing to that work by our own research. To society, being a historian might come across as wanting to relive the past in any form possible, whereas the university might hope to emphasize teaching and cultivating the next generation of historians. Though we would perhaps like to see ourselves as working in the archives, with all the time in the world to focus on the sources, the humorous reality of what we actually do depicted by the last picture is that we are most often sitting alone at our work in some corner somewhere, with endless articles piled up around us, with little time to actually read all of them.

Though the drawing of Constance, of course, cannot be equated with the meme above as such, and though the perspectives presented by the drawing are slightly different, their similarity in form and language still tickled my thoughts. This led me to ponder how to approach the drawing. What does the drawing tell us about Constance and what kind of perspectives does it highlight? And what does the artist want to say about Grace, the other figure in the drawing? Answering these questions is difficult, for despite the familiarity of the form, the drawings might not follow the same pattern as the type of meme presented above, and the perspectives they present are in no way apparent. The drawings are still, it seems apparently intended to be humorous, and an attempt at following their comical narrative offers at least some guesses or potential interpretations of the world of female students in this context.

Analyzing the drawing top-down, the first line of faces features two similar expressions with downcast eyes, though the one on the left is drawn slightly more from the profile, while the one on the right meets the gaze of the viewer more directly. The latter, however, resembles a sketch, with fainter lines and a more unfinished look, and in my view, the text “Constance as she is” refers to the first portrait. The figure with hair pinned up seems serene and solemn, even somewhat majestic, controlled, and composed, adhering to the contemporary feminine expectations of integrity, delicacy, morality, and grace.5

Beneath these portraits is another one with the text “Constance as she is not” and it is somewhat confusing– at first look, it does not seem to differ from the previous ones in any major way. The main difference is that her eyes are open and her gaze is directed to the side. This portrait is also extended down to the shoulders. But when it comes to her expression and demeanor, the figure is still serene and dignified with symmetrical facial features and well-groomed hair, in a very similar way to the previous portraits. The Constance at the bottom of the page, however, is a completely different character. She is boisterous and slovenly and has a hawknose and a wild grin. All the serenity of the previous drawings is gone. Her hair is wildly flowing in all directions, but the mischievous look on her face hints that she is okay with this.

What kind of interpretation do the pictures allow? What do they tell us about Constance? One potential frame is that they depict her as a sleepyhead. In the topmost drawing, the figure’s gaze is not downcast, but her eyes are closed – Constance is asleep. The middle portrait then shows a state Constance is never in – wide awake, alert, calm – whereas the last figure reveals Constance’s true nature. She has overslept, and has not had time to do her hair, but is mischievously ignoring all criticism on the topic as she rushes to breakfast before lectures begin. This interpretation reflects the humor present everywhere in the scrapbooks as well as the student life at large at Bryn Mawr, for other students often became the target of jokes and mischief.6 Humor often plays with gender, reveals norms, and turns tables.7 In this context, the expectation of controlled and refined femininity allowed laughter, when refinement was replaced by wild energy and nonchalant charm. The laughter was, it seems, the kind Constance could join herself.

But who then is Grace, the other figure? And what does the text “Grace with a D? E? Expression?” refer to in her case? In the portrait that presumably depicts Grace, the most obvious features are a substantial nose as well as a fashionable pompadour hairstyle, where hair was wrapped around the so-called “hair rat” that added volume to the updo. The drawing is caricature-like in a similar way to the last drawing of Constance, but the lack of other pictures as well as the numerous question marks attached to it hamper interpretation. The capitals D and E might refer to other students, whose company might affect Grace in a certain way, but the article “a” gives the assumption that it is followed by a noun, not a name. Grace’s expression, to my eyes, is grinning, kind, and maybe even slightly affectionate. Perhaps the question marks reveal that the artist was not sure what they wanted to say. The text next to the two bottom-most drawings is different handwriting than the texts above, so they might be drawn by a different person as well.

The series of pictures was potentially finished gradually and developed from doodling during a lecture into an inside joke that only a few could understand in its entirety. The yearbook of the class of 1903 reveals that two members of the class were Constance Davis Leupp and Grace Lynde Megis, who might have been the inspiration behind the drawings, but even of this, there is no certainty. From the historian’s perspective, the lack of information that could help with deciphering the drawings is somewhat frustrating, though very understandable. If one of my own doodles from the margins of my lecture notes were analyzed by someone a hundred years in the future, understanding it fully would be close to impossible. Primarily created for the eyes of a few friends, no written explanations for the context would be necessary. Viewed as a part of the construction of educated femininity in the way I have done, the drawings do offer some ground for understanding the dynamic between the refinement and graceful presence that was expected of the students by their educators and the boisterous spirit of the student life. The ideal of demure and obedient femininity had to yield as female students made fun of one another and were not too keen on following all the rules of the college. And even if I was left wanting for precise answers at the end of my archival trip, at least the drawings offered me a fun exercise in interpretation, as they seemingly combine past and present forms of humor.

- A great digitized example of a student’s scrapbook is the scrapbook of Jean Scobie Davis, Bryn Mawr Class of 1914, found here https://digitalcollections.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/object/bmc65178. More on scrapbooks as a way of record keeping for women in the context of the suffrage movement, see Watton, Cherish. “Suffrage Scrapbooks and Emotional Histories of Women’s Activism.” Women’s History Review 31, no. 5 (2022): 1028-46. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2021.2012343. ↩︎

- Edith Dabney (Ford) scrapbook, BMC-9LS-9, Box: 1. Bryn Mawr College. ↩︎

- Benveniste, Alexis. “The Meaning and History of Memes” in The New York Times Jan. 26, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/26/crosswords/what-is-a-meme.html (visited Nov. 21, 2023) ↩︎

- For more on civilization, see Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. ↩︎

- Lowe, Margaret A. 2003. Looking Good: College Women and Body Image, 1875–1930. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 56–57. ↩︎

- Edith Dabney’s scrapbook also contains a note that was maybe attached to her door at some point during her studies, jesting with how she had become a “victim of higher education” and suffered from insanity as a consequence. Edith Dabney (Ford) scrapbook, BMC-9LS-9, Box: 1. Bryn Mawr College. ↩︎

- Korhonen, Anu. Fellows of Infinite Jest: The Fool in Renaissance England. History of the Innocents. Turku: Pallosalama, 1999. 11–29. Korhonen, Anu. “The Witch in the Alehouse: Imaginary Encounters in Cultural History.” In Historische Kulturwissenschaften: Positionen, Praktiken Und Perspektiven. Edited by J. Kusber et al.: Mainzer Historische Kulturwissenschaften, 2010. Passim. ↩︎