Society usually accompanies the introduction of new technologies with both excitement and suspicion, being simultaneously driven by an enthusiasm for the possibility of improvement, as well as profoundly discomforted, with a sense of having little or no control over the direction of radical changes. 5G antennas are a very recent example of this dualism. On one side, a vast portion of people warmly welcome faster internet; on the other, 5G fears led to several cases of vandalism toward these antennas, from being simply covered in graffiti to even being burned down. This latter negative sentiment regarding technological improvement and, to some extent, science, has begun to be known by a 20th century neologism: “technophobia”.

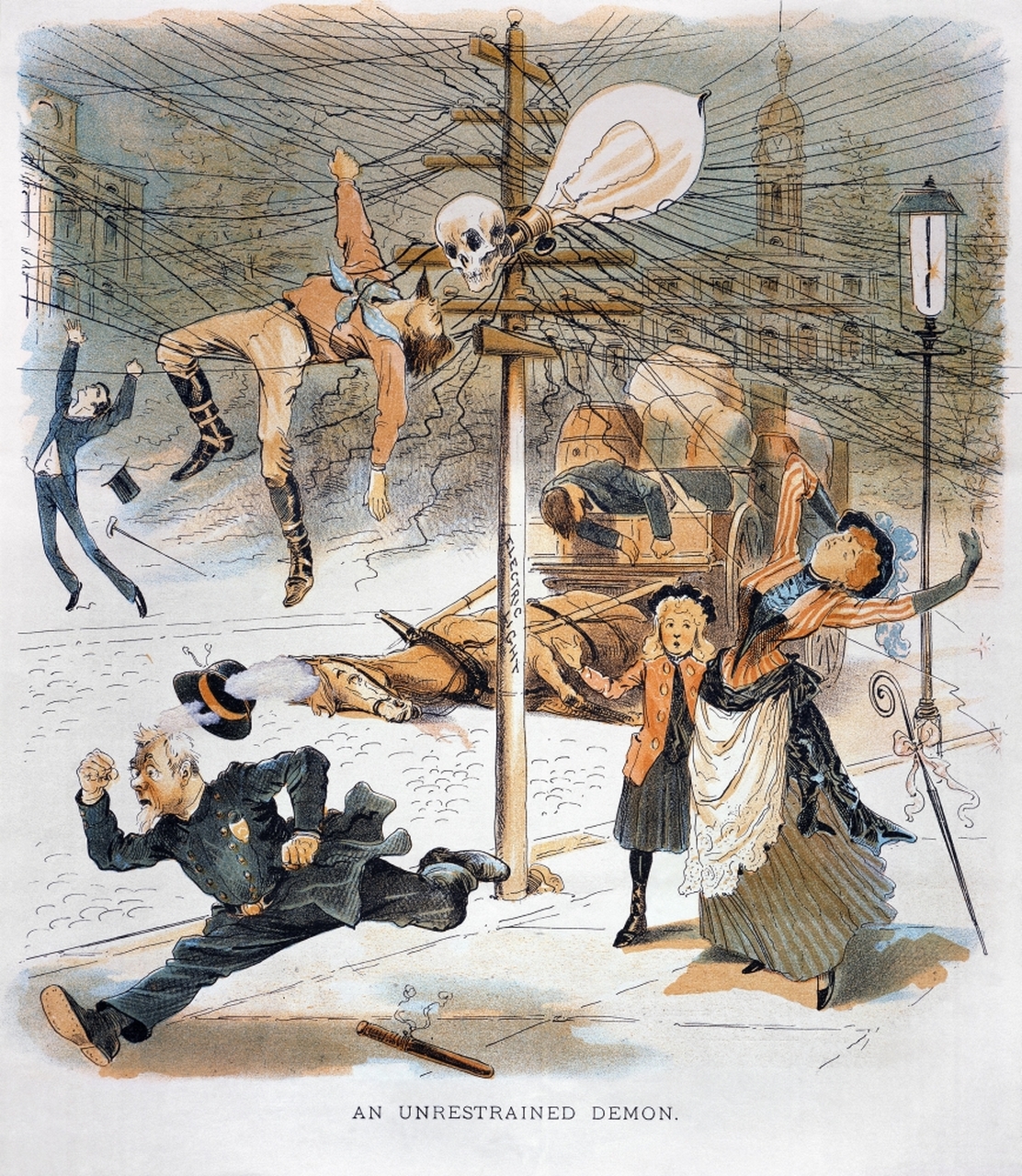

History, however, shows that technophobic feelings are not a novelty, and this is particularly evident when focusing on the reception of electricity in the 19th century. Starting with the invention of the voltaic pile and ending with the discovery of the electron, and the multi-faceted commercial and public use of electrical energy, the 19th century stands as a revolutionary period for science and society. For example, the introduction of the telegraph started to annihilate distances between people and represented an unprecedented advancement in the way humans communicated. The telegraph also revolutionized landscapes, panoramas, and city environments, due to the installation of poles connected by dense networks of wires. And it was exactly these poles and wires that drove the public’s fears, as the two following examples will show. The first example deals with electricity in literature, describing how public ideas on electricity gravitated toward a negative attitude. The second example reports a real event that happened in New York City, which led the journal Judge to publish the illustration below, showcasing just how fearful society had become of the prospect of electrical wires.

Technophobia in literature: an example from the Verismo movement

Electricity has been present in non-technical literature since the 18th century. Thus, literature can mirror how the public conceived of electricity and illustrate how these conceptions underwent a subtle but pivotal change. During the beginning of electrical science, society regarded electricity as strictly connected with vital forces: for example, after the German experimenter G. M. Bose introduced “male” and “female” electricity to explain various electrostatic phenomena, electricity became the subject of lewd literature. It was identified as a source for life, with natural references to friction, the only mechanism apt to produce electricity known at the time:

What makes our first felicity,

But this pure electricity,

Divested of all fiction:

Motion makes heat, and heat makes love,

Creatures below, and things above,

Are all produc’d by friction.

(L. Lovejoy, extract from “An Elegy on the Lamented Death of the Electrical Eel, or Gymnotus Electricus”, 1777)

With this fact in mind, it is extremely evident how the following century entailed a radical conceptual shift in how people perceived of electricity. By the 19th century, electricity became directly connected to death, and obscure, evil forces. Probably the most famous example of this new conception reaching the public mainstream is Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” (1818), where an electrical shock from lighting allowed the monster to gain life from death.

This shift in public ideas regarding electricity is even more evident when dealing with the reception of innovative electrical technology, such as the telegraph. A remarkable example can be found in Giovanni Verga’s 1881 novel “I Malavoglia”. Verga is one of the most notorious Italian writers of the second half of the 19th century and his work is extensively studied during the last year in every Italian high school. What is particularly interesting is his explicit adhesion to the Italian literary movement known as Verismo, which owes a lot to French Naturalism. Indeed, Verismo aimed at portraying society in the most objective way possible, dealing with the lives and tales of peasants and members of the humblest social classes. Therefore, Verga, together with the other verists, intended to represent the real voice of these poor and simple characters, and it is reasonable to assume there is a strict connection between what Verga makes his characters think and say, and what people of the age actually thought and spoke. In “I Malavoglia”, Verga describes the vicissitudes (mainly misfortunes) of a poor family of Sicilian fishermen living in Aci Trezza, a small village near Catania. The following quote, translated from Italian, works as an allegory for the characters’ ideas on technological innovation, in this case represented by the telegraph, introduced some twenty years earlier in Sicily.

Everyone told their troubles, also to comfort the Malavoglias, who were not the only ones to have them. ‘The world is full of troubles; some have few and some have many’ and those who were outside in the courtyard looked at the sky because another little rain would have been as necessary as bread. Padron Cipolla knew why it didn’t rain as much as before. — It doesn’t rain anymore because they put that bloody telegraph wire, which pulls all the rain and takes it away. […] Don’t you know? The telegraph carries news from one place to another; this happens because inside the wire, there is a certain juice like in the vine branch, and in the same way, it pulls the rain from the clouds and takes it far away, where it is needed more; you could go ask the pharmacist who said it; and for this reason, they had made the law that whoever breaks the telegraph wire goes to jail. — Then, even Don Silvestro didn’t know what to say anymore and kept quiet. — Saints of Paradise! They should all be cut down, those telegraph poles, and thrown into the fire! — Compare Zuppiddo began, but no one paid attention, and they looked into the garden, to change the subject.1

In this fragment, we encounter three Aci Trezza inhabitants: Compare Zuppiddo (a highly specialized artisan), Don Silvestro (an important politician), and Padron Cipolla (the richest man in the village). They are three high-profile citizens, yet they are extremely superstitious and have an ingrained mistrust of innovation. Moreover, to enforce his position regarding the dangers of the telegraph, Padron Cipolla refers to the pharmacist’s statements, who is the closest the village has to scientific authority, and clearly also knows nothing about the new technology. So, the pharmacist’s false status as an expert feeds into misinformation and contributes to the spreading of irrational fear among other inhabitants. Finally, it is interesting to note how strongly Padron Cipolla and the pharmacist’s theory of “induced drought” resembles present-day conspiracy theories on governments’ control over the weather – and who knows what they would write on their social media profiles, had they lived today…

Technophobia reaches the news: the tragic tale of John Feeks

To expand this short and limited account of electrical technophobia during the second half of the 19th century, the New York “wire panic” period serves as a great example. There are many differences between the fishermen of Aci Trezza and the residents of New York, obviously; yet fear of electricity in the 19th century finds a strange connection between these two realities. In Sicily, we found ourselves dealing with paranoid and misinformed theories. We shall see that the case is different for the Big Apple, where it was real events that shaped public perception. The focus here will be on just one peculiar example: the tragic tale of John Feeks.2

This story takes place in a New York City already tangled in electrical wires; some of these having already caused public discomfort when particularly strong storms tore down wooden poles carrying high-voltage alternating-current cables used for streetlights. In an article published on January 23rd, 1889, the New York Tribune reported a diffuse feeling of fear: “The simple truth is that everybody who ventures upon streets in a heavy storm runs a risk of making his next exit from home in a coffin”. Yet, the episode that caused the most hysterical public reaction was the bitter, though spectacular, death of John Feeks. According to the Tribune, published two days after the tragic event, it caused “many unmistakable indications of popular agitations and anger” that had not been seen in decades.

It was October 11th, 1889, and John Feeks, a lineman working for Western Union, the biggest telegraph company of the age, had been assigned a task for that day: untangle some wires on the top of a telegraph pole. Telegraphs operate at low voltages, so the only risk, John thought, would be slipping and falling. So, John decided not to wear insulating rubber boots and gloves – the standard safety equipment – but rather a pair of boots with metal spikes on the tips, to better climb and adhere to the pole. Unfortunately, John did not know that a few blocks away, due to strong winds, the night before one of the tangled wires he was to work on had made contact with a high-voltage streetlight wire. So, when the lineman accidentally slipped, he tried to avoid the fall by grabbing onto the first thing he could reach: a wire. This all happened at lunch hour, on one of Manhattan’s busiest streets, and many people witnessed the gruesome and traumatic spectacle. As Nellie Bly, a journalist for the New York World who witnessed the event, reported, John was immediately electrocuted and died with multicolored sparks emanating from his hand and quickly spreading over his entire body, with the wires piercing deeply into his flesh. More than an hour passed before another lineman, this time wearing all possible safety equipment, went to remove the dangling body of poor John.

Public opinion was unanimously horrified, and citizens were more frightened than ever. “Any moment may bring a similar horrible death to any man, woman or child in the city” reported the New York World the day after. Electric streetlights became “a fearful source of death, and a constant menace to the lives of our fellow citizens”, as the Tribune proclaimed on October 15th, 1889. “Any metallic object – a doorknob, a railing, a gas fixture, might at any moment become the medium of death” declared Mr. Thomas Edison in the same journal, published on December 3rd, 1889, enforcing his position against the use of alternate current and in favor of the exclusive use of direct current – this being an episode of a famous debate that happened to be known in literature as the War of the Currents.

Panic spread rapidly. The following quote from the December 14th, 1889, Harper’s Weekly is particularly descriptive of this paranoic climate: “Nearly every wire you see in the open air is thick enough and strong enough to carry a death-dealing current. As things are at present, there is no safety, and danger lurks all around us. It may never reach you, or you may go on for years unhurt, but when the moment comes you are killed instantly. You may touch a wire with your finger, and, though you be on the tenth floor of a building, you may be killed instantly … A man ringing a doorbell or leaning up against a lamp post might be struck dead any instant”. On January 19th, 1890, the World reported that citizens had become so terrified, paranoid, and irrational that they destroyed and threw away their telegraphic devices and phones “as if the little wires which connect them went straight to the river of death”.

Judge Magazine published two illustrations shortly after the death of John Feeks, and they are very symptomatic of the public feelings concerning electricity and wires. The first one, “An unrestrained demon”, presented at the beginning of this article, depicts electricity in the form of a monster resembling a spider, extending its death web to reach men, women, and even animals. This vignette illustrates the widespread fear that the presence of electrical wires meant no one would be safe on New York’s streets anymore. The second illustration confronted the issue with much more irony, offering a “simple” solution to the danger of being suddenly electrocuted: rubber suites and vests, resembling those of deep-sea divers, to be worn constantly, in every public scenario, by men and women, and even by horses, cats, and dogs.

Concluding remarks

Electricity permeates our everyday lives – even reading this blog post would be impossible without it. Moreover, it is now common knowledge that electricity can be very dangerous if treated improperly. So, it is quite logical to understand why such a force of nature, often invisible, could involve extremely fearful and paranoid feelings in societies facing its benefits and dangers for the very first time.

There exists an intricate interplay between technological advancements and how the public receives, adopts, and utilizes new technologies – and this is particularly evident when focusing on the mass adoption of the electric telegraph. The examination of technophobia in literature, illustrated through Giovanni Verga’s “I Malavoglia”, reveals on one side the deeply ingrained fears of innovation that permeated rural societies, but also that these fears were exacerbated by very limited access to scientific knowledge. The tragic tale of John Feeks exemplifies the tangible consequences of public apprehension in a metropolitan setting following an event that went “viral” in the media of the time. These two examples show how technophobia and, more specifically, fear of low-voltage telegraph wires, was a widespread phenomenon that cut across various social and geographical boundaries. Despite the reasons behind these feelings being enormously different between Aci Trezza and New York, similar feelings of mistrust, paranoia, and anxiety existed in both, creating a connection between these two antipodal realities.

- 1“Ognuno raccontava i suoi guai, anche per conforto dei Malavoglia, che non erano poi i soli ad averne. «Il mondo è pieno di guai, chi ne ha pochi e chi ne ha assai», e quelli che stavano fuori nel cortile guardavano il cielo, perché un’altra pioggerella ci sarebbe voluta come il pane. Padron Cipolla lo sapeva lui perché non pioveva più come prima. — Non piove più perché hanno messo quel maledetto filo del telegrafo, che si tira tutta la pioggia, e se la porta via. […] Che non lo sapevano che il telegrafo portava le notizie da un luogo all’altro; questo succedeva perché dentro il filo ci era un certo succo come nel tralcio della vite, e allo stesso modo si tirava la pioggia dalle nuvole, e se la portava lontano, dove ce n’era più di bisogno; potevano andare a domandarlo allo speziale che l’aveva detta; e per questo ci avevano messa la legge che chi rompe il filo del telegrafo va in prigione. Allora anche don Silvestro non seppe più che dire, e si mise la lingua in tasca. — Santi del Paradiso! si avrebbero a tagliarli tutti quei pali del telegrafo, e buttarli nel fuoco! — incominciò compare Zuppiddo, ma nessuno gli dava retta, e guardavano nell’orto, per mutar discorso.”

G. Verga, I Malavoglia (1881). ↩︎ - To deepen this topic and discover the sad story of John Feeks more in detail, I suggest two publications: J.P. Sullivan’s article Fearing Electricity. Overhead Wire Panic in New York City (IEEE, 1995), and M. Essig’s book Edison and the Electric Chair. A Story of Light and Death (Walker & Company, 2003). These publications served me also as the sources of newspapers and journals I am citing later in this paragraph. ↩︎