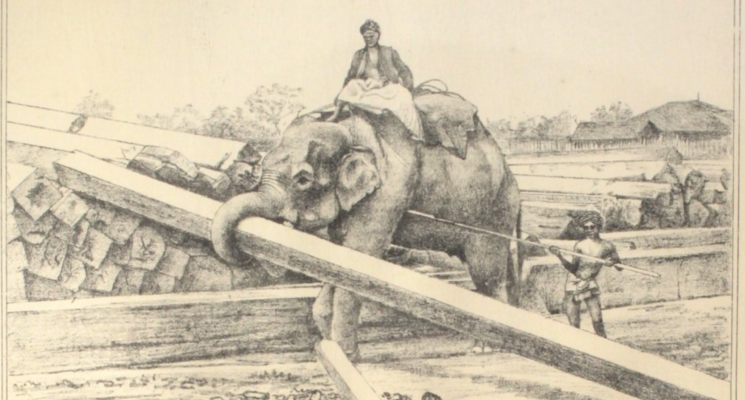

To nineteenth-century colonial Britons, the elephant was of great importance. Not only were these giants widely used in colonial enterprises such as the army and timber industry. The animal also figured prominently in the visual and literary culture of that time. In the British Raj, the theme of human domination over other animals served to ratify colonial hierarchies.[1] By presenting native attitudes towards animals as lazy, cowardly, and effeminate, and by juxtaposing these attitudes with the moral superiority of India’s colonizers, stories and pictures produced in the Raj provided a rational and legitimization for Britain’s colonial rule.

Yet, Britons in India faced a problem. For reasons unknown, elephants in service of the colonial government died in great numbers. After 1850, in reaction to this challenge, colonial officials established a body of scientific literature on elephant management and disease. It was during the same period—the aftermath of the 1857 Revolt—that the number of veterinarians in India grew gradually.[2]

One of the products of this increased colonial interest for elephant disease was John Henry Steel’s 1885 A Manual of the Diseases of the Elephant and of his Management and Uses. Printed at the Lawrence Asylum Press in Madras and approximating two hundred pages, this book once presented a cutting-edge scientific study of elephants. In Steel’s view, the colonial government had the responsibility to support his studies: “The patients are very valuable, and mostly belong to the Government; it therefore is incumbent upon the authorities to do their duty, and make arrangements for the scientific and systematic study of the disease of the elephant”.[3] What intellectual building elements, particular to his time and generation, did Steel deploy to render the diseases of elephants intelligible?

Little is known about John Henry Steel’s life and career. He graduated from Royal Veterinary College in 1875 at the age of twenty. As a Demonstrator of Anatomy, the young man worked at London College, until he went to serve in India in 1882.[4] Apart from producing treatises on several beasts of burden, dogs, and sheep, Steel founded The Quarterly Journal of Veterinary Science in India and Army Animal Management. In Steel’s view, this journal was of crucial importance to the establishment of veterinary science in the Raj. Over the years, army veterinarians had gathered invaluable information on the diseases and treatment of animals, but as long as their knowledge remained concealed within private journals and notebooks, it was worthless to the profession as a whole.[5] Knowledge must circulate in order to be useful. Steel maintained that medical knowledge developed in three stages: individual studies produced by laymen, examinations by “regularly educated medical men,” and the “scientific and practical dealing with diseases on […] the basis of accurate observation, appreciation of previous work, and knowledge of scientific methods”.[6] It was up to Steel to launch the study of elephants into its third phase.

A Manual of the Diseases of the Elephant was divided in two parts. Steel devoted part one to the elephant’s natural history and its management and uses, especially by the army. The author discussed a wide range of practical issues, such as the determination of an elephant’s age, nutrition and sleep, and the construction of elephant sheds. Part two contained the actual medical section of Steel’s treatise. After Steel provided some general considerations and a brief examination of the general signs of elephant illness, the veterinarian physician discussed elephant diseases according to several bodily “systems” and “apparatus”. Examples were the locomotive system, the generative system, the respiratory apparatus, and the urinary apparatus. What made Steel’s study “scientific”—and hence why he believed it was to be preferred over the years of experiences accumulated by native Indians—was exactly its systematics. Steel wrote that until the study of elephant diseases “is made on a scientific basis, the management of elephants under disease must remain somewhat empirical, and the man best acquainted with the manners and habits of the animal will have the advantage”.[7]

Like many of his contemporaries, Steel imagined elephants to be archaic creatures whose power and skills were rendered redundant by the progress of industrialized modernity. He described the animal as “an anachronism [which] stands isolated as a generalized ungulate, the closest relatives of which have long ago succumbed to the greater energy of higher specialization of the hoofed animals, which we find so well adapted to the present state of our earth”.[8]

Yet despite this observation, Britons in India imagined the elephant to be a very useful creature that was in perfect harmony with large parts of India, which, after all, was thought to be just as primitive as the elephants themselves. Many Britons pictured India to be a land untouched by history. Indeed, in the words of author Charles Knight, India was the country “where nothing changes,” both culturally and natural historically.[9] In the colonial mind it therefore made perfect sense to use elephants, at least in the colony. Steel described elephants as living anachronisms who had succumbed to the energies of natural progress, but, he added, they were “noble” anachronisms, “extremely useful” in certain parts of “our Indian Empire”.[10]

Steel maintained that the high death rates among government elephants was a logical consequence of their evolutionary backwardness. Britons took elephants from their native wild and submitted them to “conditions of domestication without those hereditary adaptations to the domesticated state which we find in most of our other beasts of burden”.[11] Elephant diseases, in other words, resulted from an elephant’s evolutionary incapability to cope with civilization’s demands. Steel’s understanding of elephant diseases echoed the latest medical theories from the metropole, where representatives of the medical profession argued that “[a]s civilization advanced, life became more complex, more ‘unnatural’, faster-paced, more unsettled, more stressful, less stable,” and hence a source of physical and especially mental disorder.[12] Once put to work by the colonial government of India, wild elephants were forced to live unnaturally and, according to Steel, this resulted in many diseases and injuries. Civilization had its discontents, apparently for humans and animals alike.

Still, these remarks provided only part of Steel’s account of the etiology of elephant diseases. Steel laid particular emphasis on the “epizootic and communicable nature” of diseases, which, the author wrote, had been ignored until quite recently.[13] In the years preceding the publication of Steel’s manual, T. Spencer Cobbold had argued in two publications that elephants suffered from a wide range of parasites which caused epidemic diseases.[14] A graduate from Royal Veterinary College, where Cobbold was Professor of Botany, Steel adopted some of Cobbold’s ideas. An illustration is Steel’s discussion of anthrax.[15] Steel described anthrax as due to “fungal organisms” or “parasites” that entered the body through small wounds and scratches. According to the author, many instances of death attributed to various causes by various writers had in fact been caused by this “parasite”. Steel illustrated this point by discussing a number of “native” diseases such as “Ghut bhao”, “Jolay-ka-murz”, and “Zaarbahd”. In fact, Steel claimed, all these were caused by the anthrax fungi.

However, despite its emphasis on the epizootic nature of elephant disease Steel’s account was foremost shaped by another intellectual building element: the trope of the lazy mahout. Mahouts were elephant drivers employed by the colonial government and responsible for the safety of elephants. Colonial treatises on elephants rarely failed to single out mahouts as the cause of diseases and injuries. New scientific discoveries such as parasites and bacteria could be easily reconciled with the figure of the lazy mahout. Steel maintained that “with regard to causes of disease, the elephant when properly managed very seldom suffers from disorders”. [16] From this, the veterinarian drew the conclusion that derangements and injuries were the result “of want of care through laziness or indifference, of willful [sic] injury or mismanagement, or of culpable ignorance of the means of preserving health”.

Thus, in analyzing the origins of encephalitis—inflammation of the brain and its membranes—Steel listed causes such as overexposure to the sun, overfeeding, and overstimulation by means of spices and other stimulants.[17] Epizootic disorders, on the other hand, although strictly speaking not caused by mahouts, often resulted from the fact that attendants did not take proper hygienic and preventative measures into consideration. The author recalled one time seeing a number of bullocks affected with foot and mouth disease who were “isolated” by putting them among the elephants.[18] For these reasons, Steel considered it pivotal to examine the mahout with regard to his knowledge about elephants. The attendants were well paid, he reasoned, and therefore were obliged to understand their work thoroughly.[19]

Steel’s manual was part of a larger body of veterinarian literature on elephants. Other examples include G.P. Sanderson’s Thirteen Years Among the Wild Beast of India (1879), G.H. Evans’ A Treatise on Elephants (1901), and W. Gilchrist’s A Practical Memoir on the History and Treatment of the Diseases of the Elephant (1841). Although these treatises differed from one another in a number of ways, they were strikingly similar in other ways too. All these men conceived the elephant to be an animal that belonged to the past. Once its strength and size had made the animal a valuable beast of burden, but thanks to the development of modern technologies these characteristics had been rendered redundant. These noble attributes nevertheless fueled the idea that elephants became sick only rarely. Indeed, in the words of Steel, “the elephant when properly managed very seldom suffers from disorders”. In other words, the elephant was a noble savage: simple and strong, yet healthy and most of the time friendly.

At the same time, this pristine image conflicted with the everyday experience of government elephants dying in great numbers. Colonial officials tackled this issue in two ways. On the one hand, veterinarians maintained that disease resulted from the transition from nature to civilization. British imperialism forced elephants to live unnaturally under pathological conditions. On the other hand, Steel and others argued that elephant disease was the result of misconduct by mahouts.

This maltreatment of animals would be caused by two failures on the part of native attendants: one epistemological, one moral. First, from a colonial, “scientific” point of view, native expertise was—following Steel—“somewhat empirical” and failed to grasp the systematics behind animal physiology. Second, even if mahouts would have grasped the complexity of elephant health and disease, they would have failed to care for their animals, because they were lazy and idle. During a time when the number of veterinarians in British India was growing, these professionals justified their presence in the colony by juxtaposing themselves with the ignorant and lazy mahout.

o-o-o

This essay is part of an extensive discussion of colonialism, veterinary science, and contested elephant expertise in the British Raj. Under the title of “A Noble Anachronism: Elephants and Veterinary Medicine in the British Raj, ca. 1840-1900,” it will appear in Colonialism and Official Forms of Knowledge: The British in India, edited by Vinay Lal and under contract by Primus Books.

[1] Shefali Rajamannar, Reading the Animal in the Literature of the British Raj (New York: Palsgrave Macmillan, 2012).

[2] In the aftermath of the 1857 Revolt the relative portion of cavalry regimes was raised and hence more veterinary practitioners were needed. See: Saurabh Mishra, ‘Beast, Murrains, and the British Raj: Reassessing Colonial Medicine in India from the Veterinary Perspective, 1860-1900’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine 85 (2011), 587-619, 594.

[3] John Henry Steel, A Manual of the Diseases of the Elephant and his Management and Uses (Madras: W.H. Moore, 1885), 2. Emphasis copied from original text.

[4] For a short biography, see “One of the Professions Youngest and Brightest Ornaments”. <https://rcvsknowledgelibraryblog.org/2013/09/24/one-of-the-professions-youngest-and-brightest-ornaments/> (Last visited on October 1, 2016.)

[5] Steel, A Manual of the Diseases of the Elephant, 4.

[6] Ibid, 1.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., xvii.

[9] Charles Knight, The Elephant as He Exists in a Wild State, and as He has been Made Subservient, in Piece and in War, to the Purposes of Man (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1848), 76. Also see: Ronald Inden, Imagining India (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992).

[10] Steel, A Manual of the Diseases of the Elephant, xvii; ix.

[11] Ibid., 2.

[12] Andrew Scull, Madness in Civilization: A Cultural History of Insanity from the Bible to Freud, from the Madhouse to Modern Medicine (Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2015), 224.

[13] Steel, A Manual of the Diseases of Elephants, 6.

[14] T. Spencer Cobbold, ’On the Destruction of Elephants by Parasites, with Remarks on Two New

Species of Entozoa and on the so-called Earth-Eating Habits of Elephants and Horses in India’, The Veterinarian 48 (1875), 1-13; T. Spencer Cobbold, ‘The Parasites of Elephants’, Transactions of The Linnean Society of London 2 (1882), 223-258.

[15] Steel, A Manual of the Diseases of the Elephant, 11-5.

[16] Ibid., 3.

[17] Ibid., 49.

[18] Ibid., 18.

[19] Ibid., xlii.