Every generation gets the self-help book it deserves. From the nineteenth-century Marriage Manual to the more recent The 4-hour Work Week (2007), books have been telling us how to cope with life. The promises of these books were—and still are—based on new or recycled knowledge about psychology, health, and business, and on common sense advice cloaked in the rhetoric of revolutionary personal change. The writers of these books were also eager to jump on the bandwagon of new tools to organise information. Or so it seems from a book that I found with the intriguing title Kartothek des Ich: A card index of the self.[1]

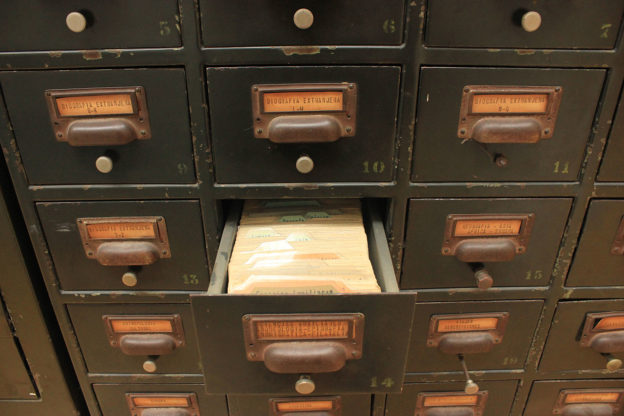

It was published in 1934 in Vienna, which was, as Markus Krajewski writes in his Paper Machines, coincidentally also the place where the first card catalogue was created in the court library around 1780. The card index was a revolutionary method to organise information: with cards as mobile building blocks it had the potential to grow indefinitely. By the 1930s, boxes with index cards could be found on many desks and in many organisations. Vladimir Nabokov used them too, to write and organise the drafts of most of his novels. Today, the system has come to the attention of historians of science because, as means to organise information, it has implications for how knowledge is subsequently retrieved, combined or forgotten.

There was little I could find about the author of Kartothek des Ich, Viktor Esdorp, until I realized that Esdorp was a pen name and anagram of Viktor Pordes, a Jewish lawyer and lecturer in Vienna and author of an earlier book about film. Pordes was a regular contributor to newspapers and wrote about legal issues, but also about more educational topics such as ‘the art of conversation’. And with Freud’s name on everyone’s lips, there must have been a market for books about self-knowledge. 1934, however, the year Esdorp’s book was published, also saw the beginning of the end of the golden age of left-wing modernism in Vienna, and this may explain why, though said to be popular and soon out of print, new editions of the book were never printed.

In Kartothek des Ich, Esdorp proposes a system that teaches the reader how to live, based on the reader’s life experience and on a precise and scientific method. Isn’t it a pity, he writes, that we only learn the art of life after a lifetime of experience, while we all wish we had had these insights earlier? Yet this is possible, Esdorp continues, if we approach our own lives with the rigor and objectivity of a scholar. All we have to do is to build a system of records, a paper account of our life.

Esdorp means it literally: for true self-improvement, his readers are advised to keep a strictly chronological and objective diary, archiving not only extraordinary events, but also the most ordinary. Self-improvers are to make day plans and reflect at the end of the day how well they executed these. They must keep track of their work and record their dreams, hopes, and questions. Once the reader has gathered all this ‘evidence’ of his own life, he can start organising and combining, with an alphabetical card index of names and subjects. And then, by looking back and browsing through the files of his own card cabinet, he gains insight into the causal relations in his past. Esdorp is vague about how exactly this insight comes about, but emphasizes that it can be used to do things differently in the future.

One wonders if anyone has ever followed Esdorp’s advice and built a file with cards named ‘My love life’, ‘How I hate my boss’ or ‘What I did on the first of June’. Esdorp seems to have overlooked that his system was far too comprehensive. Building a personal archive of day-to-day experiences would take hours every day. Card catalogues were an answer to information overload, but his system produced so much personal data that it ran the risk of soon being forgotten.[2]

The attraction of the system must have been that it was a simple and procedural method to bring self-knowledge, in an era characterized by rather high standards of intellectual and aesthetic self-fashioning and -expression. If Esdorp had lived today, he would have been a self-tracker with digital data.

[1] The German word Kartothek has not become common usage. The word Kartei is usually used for card catalogues.

[2] Books such as Alberto Cevolini’s Forgetting Machines and Rebecca Lemov’s Database of Dreams show that as substitutes for personal memory, card cabinets and databases often led to forgetting rather than remembering.